We live in an era of unprecedented environmental stress. From the pervasive impact of glyphosate and heavy metals to the disruption of our natural light environment, our bodies are constantly navigating threats unknown to our ancestors.

In response, the field of functional medicine has diligently mapped the biochemical pathways affected by these stressors. We analyze MTHFR mutations, scrutinize mitochondrial function, and optimize detoxification. Yet, for many, true healing remains elusive. Protocols provide temporary relief, only for symptoms to return or shift.

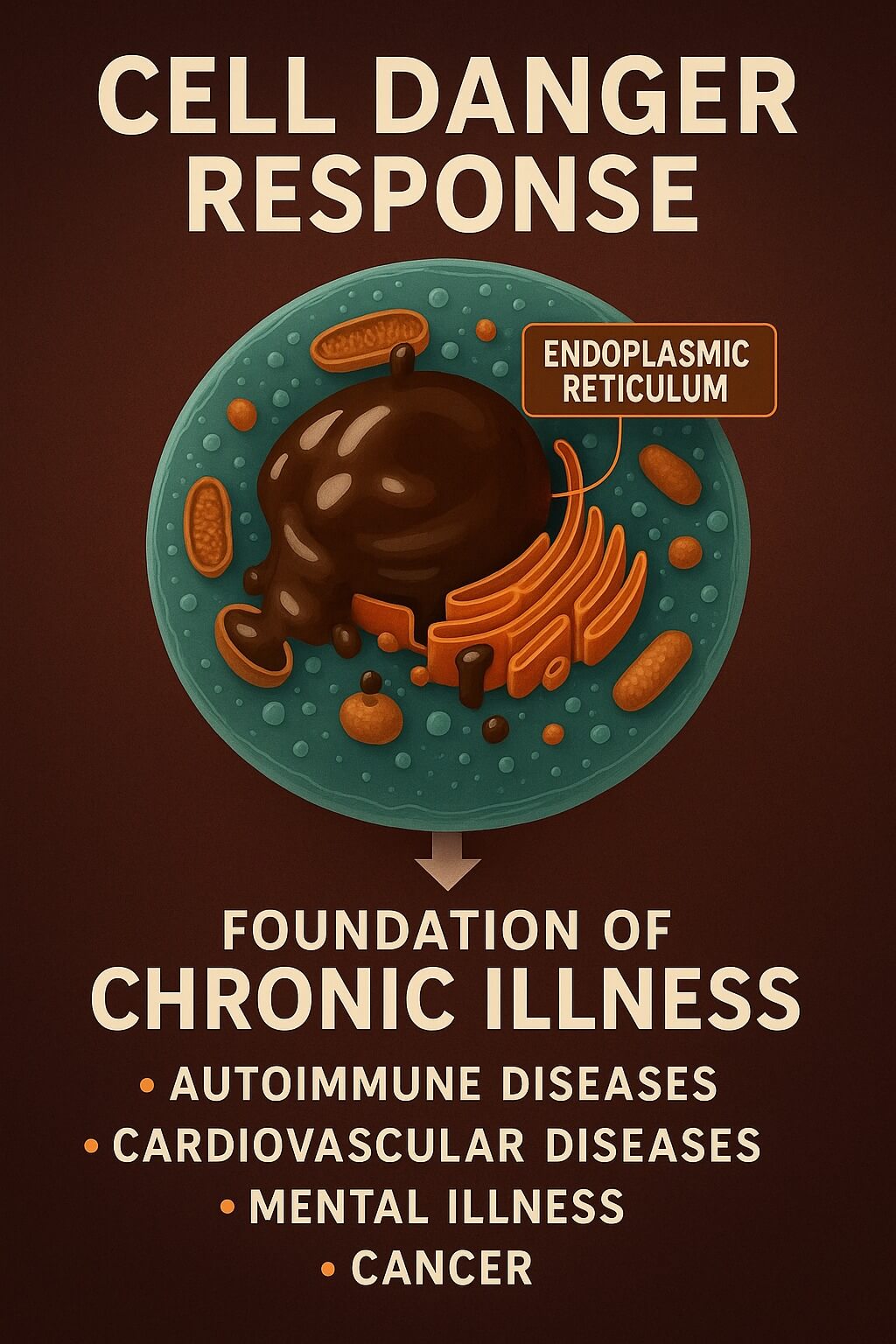

The reason is often that we are focusing on the downstream effects while ignoring the upstream, coordinated defense strategy that the body deploys in the face of danger. If we are to understand why diverse conditions—like Lyme disease, mold toxicity, and heavy metal poisoning—often look identical (It's All The Same), we must understand the Cell Danger Response (CDR).

The Paradigm Shift: The Cell Danger Response

The Cell Danger Response is a groundbreaking theory formalized by Dr. Robert Naviaux at the University of California, San Diego. It proposes that there is a universal, evolutionarily ancient response to any threat that exceeds a cell's capacity to maintain balance.

Whether the threat is a virus, a heavy metal, a pesticide, or even severe psychological trauma, the cell activates a stereotyped sequence of reactions designed for immediate survival. The CDR is a fundamental shift from a "peacetime economy" focused on growth, connection, and efficiency, to a "wartime footing" focused purely on defense.

As Dr. Naviaux outlined in his foundational 2014 paper, this response is essential for survival and healing in the acute phase. However, the CDR is designed to be temporary. Chronic illness, Naviaux argues, is largely the result of the CDR getting stuck.

Mitochondria: From Powerhouse to Battleship

The mitochondria are central to this shift. In a healthy state, their primary role is oxidative phosphorylation—the efficient production of vast amounts of ATP (energy).

But mitochondria wear many hats. They are also critical environmental sensors. When they detect a threat, they radically alter their function. They decrease oxygen consumption and shift their metabolic focus away from energy production and toward defense. They transform from powerhouses into battleships.

This intentional metabolic slowdown is a protective mechanism, designed to conserve resources, limit the production of damaging free radicals, and sequester materials that might be hijacked by pathogens.

The Danger Signal: Extracellular ATP

How do the cells coordinate this defense? The critical alarm signal is ATP itself.

Inside the cell, ATP is the currency of energy. Outside the cell, it is a potent signal of danger (a Damage-Associated Molecular Pattern or DAMP). When a cell is stressed or damaged, it releases ATP into the extracellular space (eATP). This eATP binds to specific receptors on the cell surface—a process known as purinergic signaling.

This signaling triggers a cascade of defensive actions:

- Cellular Lockdown: The cell stiffens its membranes and reduces communication with neighboring cells to prevent the spread of the perceived threat.

- Inflammation Activation: The cell releases pro-inflammatory cytokines to recruit the immune system.

- Metabolic Shift: The body enters a state of hypometabolism (fatigue).

- Sickness Behavior: At the whole-organism level, the CDR manifests as pain sensitivity, fatigue, anxiety, and social withdrawal—behaviors designed to conserve energy and focus on healing.

The Blocked Healing Cycle

In a healthy scenario, once the threat is neutralized (e.g., the infection is cleared, the toxin is removed), the healing cycle proceeds. Extracellular ATP is metabolized, the danger signals cease, and the cells return to their normal, energy-producing functions.

However, if the signaling process is disrupted, or if the cumulative load of stressors is too high, the healing cycle cannot complete. The CDR becomes chronically activated.

The cells remain in a defensive, low-energy state, constantly behaving as if the initial injury is still present. This persistent hypometabolic state—which Naviaux found is chemically similar to the hibernation-like state known as "dauer"—is the root cause of the crushing fatigue and systemic dysfunction seen in complex chronic illnesses like ME/CFS. [Source]

How the CDR Integrates the Pathway Map

Understanding the CDR helps integrate seemingly disparate areas of health research, providing a framework for why certain interventions fail while others succeed.

MTHFR, Methylation, and Glutathione

The CDR fundamentally changes how the body utilizes the folate and methionine cycles. When the CDR is activated, the cell prioritizes survival over optimization. Resources are often shunted away from methylation (which is crucial for neurotransmitter synthesis and gene regulation) and toward the transsulfuration pathway to maximize the production of glutathione, the master antioxidant. The CDR specifically produces a cascade of changes in carbon and sulfur resource allocation.

This is a critical insight for anyone dealing with MTHFR or sulfur sensitivity. Attempting to force methylation with high doses of methylfolate while the CDR is active can exacerbate the imbalance, as the cells are actively trying to direct resources elsewhere. The CDR explains why addressing genetic polymorphisms without first addressing the underlying cellular stress often yields poor results.

The Paradox of Detoxification

Many realize that environmental toxins like mercury or mold are the root of their illness. Yet, aggressive detoxification protocols often make them feel worse.

The CDR explains why: Detoxification is an energy-intensive, "peacetime" activity. When the CDR is active, the cell is in "wartime." Cellular membranes are stiffened, and energy production is downregulated. The body cannot effectively mobilize and excrete toxins while its cells are in lockdown. Forcing detoxification before the cells are ready can simply stir up toxins without efficiently eliminating them, further increasing the danger signals.

The Light Environment and Redox

The work of researchers like Dr. Jack Kruse emphasizes the profound impact of the light environment on mitochondrial health. The CDR provides the mechanistic link. Mitochondria are highly sensitive to the redox environment, which is heavily influenced by exposure to natural sunlight (especially infrared light) and disrupted by artificial blue light.

A supportive light environment improves mitochondrial efficiency and resilience, increasing the threshold required to trigger the CDR. Conversely, a disrupted light environment lowers this threshold, making the cells more likely to enter and remain in a state of defense.

Conclusion: Safety First

If chronic illness is a manifestation of a stuck Cell Danger Response, our entire approach to healing must shift. We cannot optimize a system that believes it is fighting for its life.

The primary goal of intervention is not to force pathways, aggressively detoxify, or override mitochondrial function. The goal is to signal safety.

This involves systematically identifying and removing the triggers (toxins, infections, trauma) that are keeping the alarm bells ringing. Only when the cells perceive safety can the healing cycle begin, allowing the mitochondria to switch from defense back to energy production, and restoring the vibrant health that is our birthright.