Free Glutamate and Neurological Health: Beyond Genetic Determinism

The prevailing narrative around neurological issues often points to "free glutamate" as a primary driver of symptoms ranging from migraines to autism. However, this perspective fundamentally misunderstands the role of glutamate in the body. Glutamate is the most abundant excitatory neurotransmitter in the mammalian nervous system, essential for learning, memory, and neural development. The problem isn't glutamate itself—it's the metabolic context in which glutamate accumulates when the system cannot properly regulate it. Rather than simply avoiding dietary sources or blaming genetic variants, understanding the full metabolic picture reveals actionable interventions that address root causes.

The Glutamate-GABA Balance: A System Under Stress

Glutamate and GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) form the primary excitatory-inhibitory balance in the brain. Glutamate drives neural activation, while GABA provides the brake. This isn't a static system—the enzyme glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) continuously converts glutamate to GABA using vitamin B6 (pyridoxal-5-phosphate) as a cofactor. When this conversion is impaired, glutamate accumulates while GABA becomes insufficient.

The nutrient dependencies reveal why genetic explanations are incomplete:

-

Vitamin B6 (P5P form) is absolutely required for GAD enzyme function. Up to 30% of the population has impaired conversion of pyridoxine to P5P, meaning dietary B6 doesn't translate to functional B6. Deficiency leads to glutamate accumulation and GABA deficiency simultaneously.

-

Zinc modulates NMDA receptors (primary glutamate receptors) and is required for GAD enzyme activity. Zinc deficiency, affecting 17% of the global population, increases glutamate excitotoxicity while reducing GABA synthesis.

-

Magnesium acts as a natural NMDA receptor blocker, preventing excessive glutamate signaling. Clinical studies show 48-60% of Americans consume insufficient magnesium, directly increasing vulnerability to glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity.

The genetic variants often blamed—GAD1, COMT, MTHFR—may influence enzyme efficiency, but they operate within a metabolic context. A person with "perfect" genetics but severe B6, zinc, and magnesium deficiency will experience glutamate dysregulation. Conversely, someone with genetic variants but optimal nutrient status may experience minimal symptoms. This is not genetic determinism—it's metabolic biochemistry.

Glutamate Reuptake and the Astrocyte Connection

Astrocytes, the most abundant glial cells in the brain, are responsible for clearing glutamate from synaptic spaces. They use specialized glutamate transporters (EAAT1/GLAST and EAAT2/GLT-1) to recycle glutamate, converting it to glutamine via glutamine synthetase. This glutamate-glutamine cycle prevents excitotoxicity and maintains neurotransmitter pools.

What impairs astrocyte function and glutamate clearance:

-

Oxidative stress damages astrocyte membranes and glutamate transporters. Heavy metals (mercury, lead, aluminum), pesticides, and inflammatory cytokines all increase oxidative stress, reducing glutamate clearance capacity by up to 70% in affected tissues.

-

Energy deficiency impairs the ATP-dependent glutamate transporters. Mitochondrial dysfunction from nutrient deficiencies (B vitamins, CoQ10, magnesium, iron) directly reduces glutamate uptake. This explains why fatigue and brain fog often accompany glutamate sensitivity.

-

Neuroinflammation activates microglia and reduces astrocyte glutamate transporter expression. Chronic inflammation from gut dysbiosis, food sensitivities, or autoimmune conditions creates a self-reinforcing cycle: inflammation reduces glutamate clearance, excess glutamate increases inflammation.

Research on autism spectrum disorders consistently shows reduced glutamate transporter function in post-mortem brain tissue. However, studies also demonstrate that reducing systemic inflammation and oxidative stress can partially restore glutamate clearance. The difference between these findings is critical: genetic variants may predispose, but metabolic state determines expression.

The Methylation-Glutathione-Glutamate Triangle

Glutamate serves as a precursor for glutathione, the body's master antioxidant. The synthesis pathway requires three amino acids: glutamate, cysteine, and glycine, combined by two enzymes requiring ATP and magnesium. When methylation pathways are impaired—often blamed on MTHFR variants—cysteine becomes limited, creating a metabolic traffic jam.

The interconnected pathways:

When this system breaks down—from nutrient deficiencies, toxic burden, or chronic stress—glutamate cannot be efficiently incorporated into glutathione. The result: glutamate accumulates while oxidative stress increases, creating a vicious cycle. Studies in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and autism spectrum disorders consistently show both elevated glutamate and depleted glutathione.

Clinical implications: NAC (N-acetylcysteine) supplementation at 600-2400mg daily provides cysteine, enabling glutathione synthesis and reducing glutamate accumulation. Multiple clinical trials show NAC reduces symptoms in conditions associated with glutamate dysregulation: autism (42% improvement in irritability), schizophrenia (significant negative symptom reduction), and OCD (substantial symptom reduction). This isn't managing genetics—it's providing metabolic support.

The Gut-Brain Glutamate Axis

Approximately 95% of the body's serotonin and 50% of dopamine are produced in the gut, but the gut also produces and regulates glutamate. The intestinal epithelium uses glutamate as a primary fuel source, with enterocytes metabolizing 70-90% of dietary glutamate before it reaches systemic circulation.

When gut function is compromised:

-

Intestinal permeability ("leaky gut") allows higher levels of glutamate into systemic circulation. Inflammatory conditions, dysbiosis, and food sensitivities damage tight junctions, reducing the gut's ability to metabolize glutamate locally.

-

Dysbiosis alters glutamate metabolism. Certain bacterial species produce glutamate, while others consume it. Clostridium species, often overgrown in dysbiotic states, produce significant glutamate and reduce GABA availability.

-

Inflammation from gut dysfunction activates the immune system, producing inflammatory cytokines that cross the blood-brain barrier and impair astrocyte glutamate clearance. This creates a systemic problem from a local issue.

Research on autism spectrum disorders reveals altered gut microbiome composition correlating with glutamate dysregulation and behavioral symptoms. Probiotic interventions—particularly Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species—show promise in reducing glutamate levels and improving symptoms. L-glutamine supplementation (5-15g daily) supports enterocyte health, reducing intestinal permeability and improving local glutamate metabolism.

Excitotoxicity: When Glutamate Becomes Dangerous

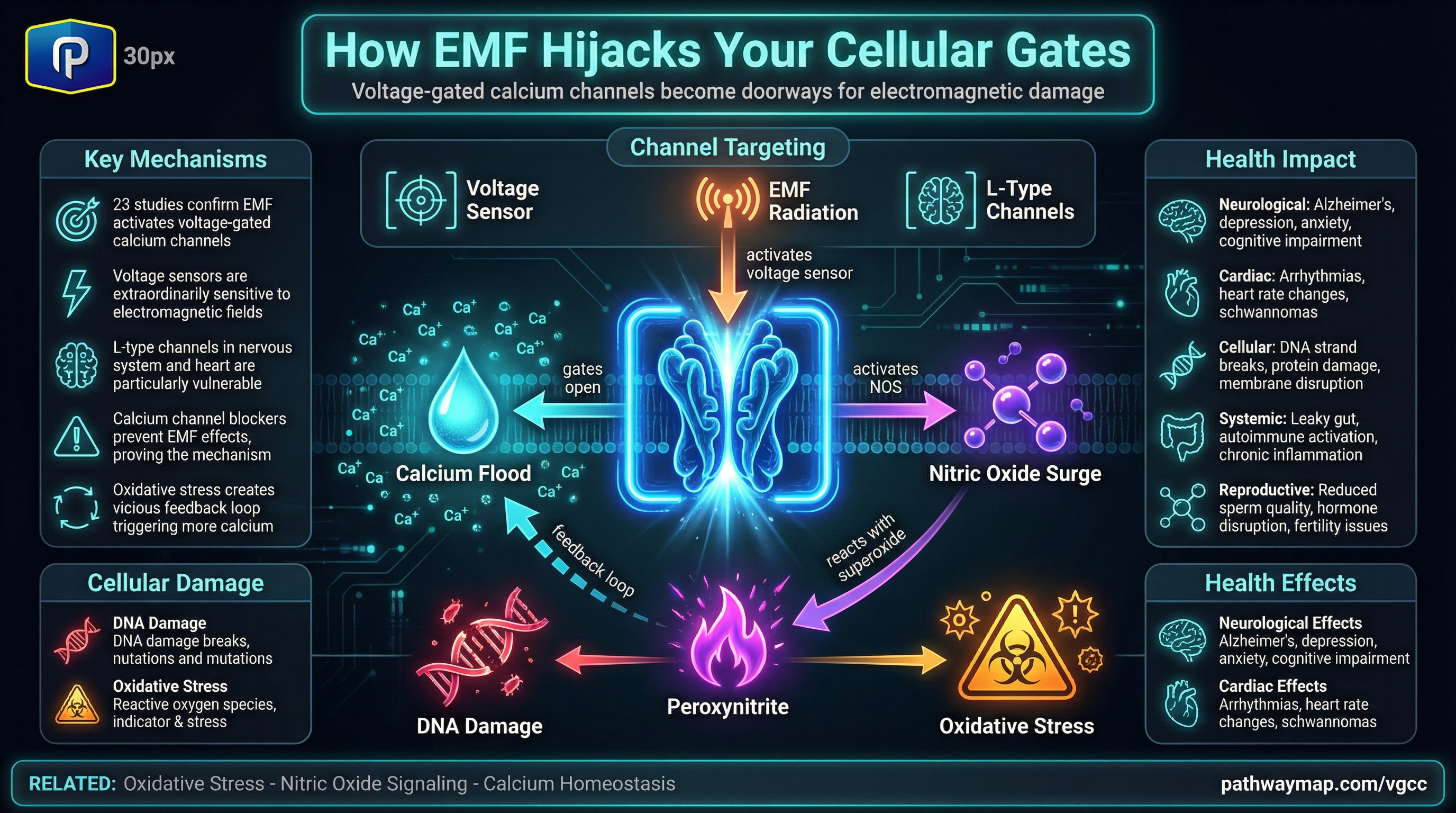

Glutamate excitotoxicity occurs when excessive glutamate overstimulates NMDA receptors, causing calcium influx that triggers cell death pathways. This mechanism underlies neuronal damage in stroke, traumatic brain injury, and neurodegenerative diseases. However, excitotoxicity also operates at subtoxic levels, creating chronic dysfunction without obvious cell death.

Protective factors against excitotoxicity:

-

Magnesium sits in the NMDA receptor channel, blocking excessive calcium influx. Magnesium deficiency removes this protection, allowing uncontrolled glutamate signaling even at normal glutamate levels.

-

Antioxidants (vitamins C and E, glutathione, polyphenols) prevent oxidative damage from glutamate-mediated calcium influx. Clinical studies show that vitamin E supplementation (400-800 IU daily) reduces excitotoxic damage in neurological conditions.

Animal studies demonstrate that combined nutritional support—B6, zinc, magnesium, antioxidants—prevents excitotoxicity more effectively than any single intervention. The system requires multiple supports, not single solutions.

MSG and Dietary Glutamate: Separating Science from Fear

Monosodium glutamate (MSG) has been vilified since the 1968 "Chinese Restaurant Syndrome" letter in the New England Journal of Medicine. Subsequent double-blind, placebo-controlled studies failed to confirm MSG sensitivity in the general population. However, in individuals with impaired glutamate metabolism—from the mechanisms described above—dietary glutamate can exacerbate symptoms.

The context matters:

High-glutamate foods include aged cheeses, cured meats, tomatoes, mushrooms, soy sauce, and many fermented foods. Elimination diets that remove these foods often provide temporary relief, but they don't address the underlying metabolic dysfunction. The goal should be restoring glutamate metabolism, not permanent dietary restriction.

Clinical observations: Individuals who improve their nutrient status and address gut health often regain tolerance to glutamate-containing foods. This supports the metabolic dysfunction model over genetic determinism.

Neurological Conditions and the Glutamate Connection

Migraines and Headaches

Multiple studies identify elevated glutamate in the brains of migraine patients using magnetic resonance spectroscopy. The cortical spreading depression that initiates migraines involves massive glutamate release. Interventions targeting glutamate metabolism show promise:

- Magnesium supplementation (400-600mg daily) reduces migraine frequency by 41.6% in clinical trials

- Riboflavin (B2) at 400mg daily reduces migraine frequency, likely through improved mitochondrial function supporting glutamate metabolism

- CoQ10 supplementation (100-300mg daily) shows significant migraine reduction in multiple studies

Anxiety and Panic Disorders

Elevated glutamate in the prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex correlates with anxiety severity. The glutamate-GABA balance is consistently disrupted in anxiety disorders, with reduced GAD enzyme activity.

- GABA supplementation shows limited efficacy because it doesn't cross the blood-brain barrier well, but supporting endogenous GABA production with B6 (50-100mg P5P daily) provides clinical benefit

- Taurine (500-3000mg daily) modulates GABA receptors and reduces glutamate excitotoxicity, showing anti-anxiety effects

- L-theanine (200-400mg daily) increases GABA, dopamine, and serotonin while reducing glutamate excitotoxicity

Autism Spectrum Disorders

Glutamate dysregulation is one of the most consistent neurochemical findings in ASD, with elevated glutamate in multiple brain regions. The excitatory-inhibitory imbalance theory of autism posits that excessive glutamate signaling relative to GABA creates the sensory and behavioral features of ASD.

- NAC supplementation (900-2700mg daily) shows consistent benefit in reducing irritability and repetitive behaviors in ASD

- Vitamin B6 with magnesium has decades of research showing behavioral improvements in autism

- Addressing gut dysfunction—common in 70% of ASD individuals—often reduces glutamate-related symptoms

Neurodegenerative Diseases

Glutamate excitotoxicity contributes to neuronal loss in Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and ALS. Memantine, an FDA-approved Alzheimer's medication, works by modulating NMDA receptors to prevent glutamate excitotoxicity.

- Curcumin reduces glutamate-mediated oxidative stress and neuroinflammation

- Green tea polyphenols (EGCG) protect against glutamate excitotoxicity through multiple mechanisms

- Comprehensive B vitamin support improves outcomes in MCI and early Alzheimer's

Practical Interventions: Supporting Glutamate Metabolism

Foundation nutrients (everyone needs adequate levels):

-

Vitamin B6 (P5P form): 25-50mg daily. Required for GAD enzyme converting glutamate to GABA. Use P5P form to bypass conversion issues.

-

Magnesium: 400-600mg daily (glycinate, threonate, or malate forms). Natural NMDA blocker and required for hundreds of enzymes.

-

Zinc: 15-30mg daily (with 1-2mg copper to prevent imbalance). Required for GAD enzyme and NMDA receptor modulation.

-

B-complex: Including B2 (100-400mg for migraines), folate (methylfolate if MTHFR variants), B12 (methylcobalamin). Supports methylation and energy metabolism.

Glutathione support:

-

NAC: 600-2400mg daily in divided doses. Provides cysteine for glutathione synthesis, reducing glutamate accumulation.

-

Glycine: 3-5g daily. Often overlooked but required for glutathione synthesis. Also glycinergic, providing calming effects.

-

Selenium: 200mcg daily. Required for glutathione peroxidase enzyme activity.

Mitochondrial and antioxidant support:

-

CoQ10: 100-300mg daily (ubiquinol form for better absorption). Supports ATP production needed for glutamate transporters.

-

Alpha-lipoic acid: 300-600mg daily. Antioxidant that regenerates other antioxidants and supports mitochondria.

-

PQQ: 10-20mg daily. Promotes mitochondrial biogenesis.

GABA modulation:

-

Taurine: 500-3000mg daily. Modulates GABA receptors and reduces excitotoxicity.

-

L-theanine: 200-400mg daily. Increases GABA and reduces glutamate.

-

Magnesium-threonate: Specifically crosses blood-brain barrier better than other forms for direct CNS effects.

Gut support:

-

Probiotics: Multi-strain formula including Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species. Reduces glutamate production and supports intestinal barrier.

-

L-glutamine: 5-15g daily. Supports enterocyte health and gut barrier function.

-

Digestive enzymes: Support complete protein breakdown, reducing peptide permeability.

Lifestyle factors:

-

Sleep optimization: Sleep deprivation increases glutamate and reduces GABA. Prioritize 7-9 hours nightly.

-

Stress management: Chronic stress elevates cortisol, which increases glutamate release. Regular stress reduction practices are essential.

The Bigger Picture: Systems Biology Over Reductionism

The "free glutamate as villain" narrative represents the danger of reductionist thinking in complex biological systems. Glutamate is essential for brain function—the problem arises when multiple metabolic systems fail simultaneously. Blaming genetics provides a convenient explanation but offers no path forward. Understanding the interconnected pathways—nutrient cofactors, oxidative stress, inflammation, gut health, energy metabolism—reveals actionable interventions.

The research consistently shows:

- Genetic variants influence enzyme efficiency but don't determine outcomes in adequate metabolic environments

- Nutrient deficiencies impair glutamate metabolism regardless of genetics

- Systemic factors (inflammation, oxidative stress, gut dysfunction) trump local genetic differences

- Comprehensive metabolic support often normalizes glutamate function even with genetic predispositions

- Dietary restriction alone fails without addressing underlying metabolic dysfunction

This isn't to dismiss genetic factors entirely. Certain polymorphisms do increase vulnerability. However, vulnerability is not destiny. The metabolic environment determines whether genetic predisposition manifests as disease or remains silent. Supporting that environment—through targeted nutrition, stress management, sleep, exercise, and toxin reduction—provides agency where genetic determinism offers only resignation.

The future of neurological health lies not in accepting genetic fate but in optimizing the metabolic systems that regulate neurotransmitter function. Free glutamate is a number in a system that isn't working right. Fix the system, and the numbers often fix themselves.

How I Support Glutamate Metabolism

I don't avoid glutamate-rich foods indefinitely because that doesn't fix the problem. Instead, I focus on supporting the systems that regulate glutamate:

Daily foundation:

- P5P (active B6) 25-50mg for GAD enzyme support

- Magnesium glycinate 400-600mg for NMDA receptor protection

- Zinc picolinate 20mg with 1mg copper

- Methylated B-complex for overall metabolic support

Glutathione pathway:

- NAC 1200-1800mg daily in divided doses

- Glycine powder 3-5g daily in water

- Selenium 200mcg daily

Energy and antioxidant support:

- CoQ10 (ubiquinol) 200mg daily

- PQQ 20mg daily

- Alpha-lipoic acid 300mg daily

Calming support as needed:

- Taurine 1000-2000mg when feeling overstimulated

- L-theanine 200mg for focus without anxiety

- Magnesium threonate before bed for brain-specific effects

Gut support:

- Multi-strain probiotic daily

- L-glutamine 5-10g daily away from meals

- Digestive enzymes with protein-containing meals

Lifestyle non-negotiables:

- Morning sunlight exposure for circadian rhythm

- 7-8 hours quality sleep

- Regular but not excessive exercise

- Stress management practices

After implementing this approach, I can tolerate aged cheeses, fermented foods, and even occasional MSG without symptoms. The difference isn't avoiding glutamate—it's having a system that can properly regulate it.

Conclusion

Free glutamate is not inherently pathological. It becomes problematic only when multiple metabolic systems simultaneously fail to regulate it—nutrient deficiencies impair conversion to GABA, oxidative stress damages clearance mechanisms, inflammation disrupts astrocyte function, gut dysfunction increases systemic load, and energy deficits prevent proper transport. These failures are addressable through comprehensive metabolic support.

The genetic determinism narrative—"you have these SNPs, therefore you'll always have this problem"—ignores the fundamental principle of biochemistry: genes load the gun, but environment pulls the trigger. More accurately, environment determines whether there are bullets in the gun at all. Optimizing nutrient status, reducing toxic burden, supporting gut health, managing stress, and ensuring adequate sleep creates an environment where even "unfavorable" genetics may not express pathologically.

This perspective shift—from fatalistic acceptance to metabolic optimization—transforms glutamate sensitivity from a life sentence to a solvable biochemical puzzle. The research supports this view: comprehensive interventions addressing multiple pathways show consistent benefit across neurological conditions associated with glutamate dysregulation. Rather than simply blaming it on genes or avoiding glutamate forever, we can build metabolic resilience that allows the system to function as designed.