TLDR: Chromium enhances insulin function through a complex called chromodulin, potentially improving blood sugar control by 10-20% in people with diabetes. While it doesn't directly interact with vitamin B12, both nutrients support energy metabolism through complementary pathways. The evidence suggests chromium works more like a beneficial supplement at 200-1,000 μg/day rather than an essential nutrient, with vitamin C significantly boosting its absorption.

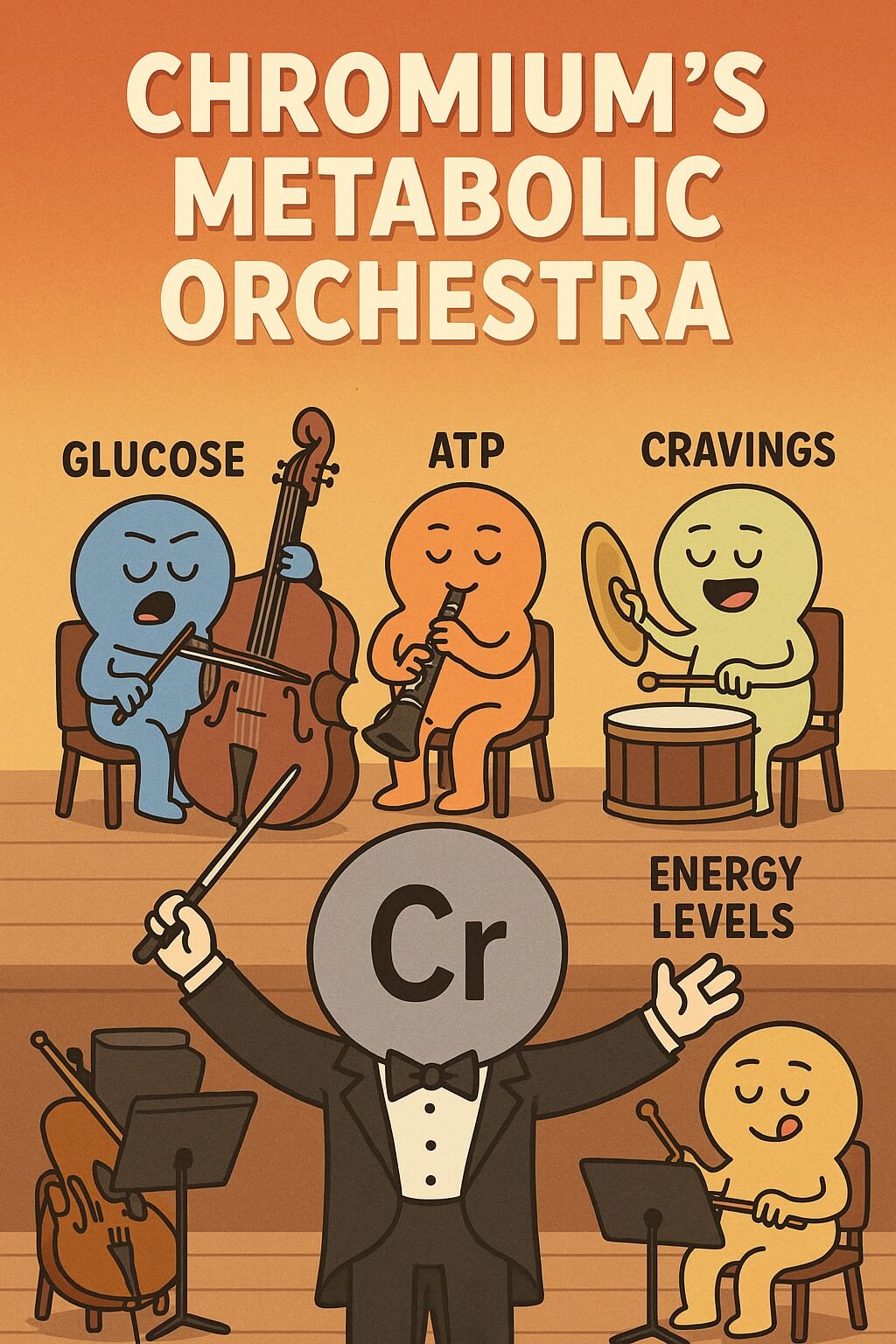

Chromium's metabolic orchestra: how this trace mineral conducts glucose metabolism and nutrient interactions

Chromium functions as a critical metabolic conductor, enhancing insulin's ability to regulate glucose while orchestrating complex interactions with other nutrients. Recent research reveals chromium works through sophisticated molecular mechanisms involving the chromodulin complex, which amplifies insulin receptor signaling up to 7-fold. While its connections to vitamin B12 are primarily indirect through shared metabolic pathways, chromium's interactions with vitamins C and niacin significantly enhance its bioavailability and effectiveness. Current scientific consensus suggests chromium provides modest but meaningful benefits for glucose metabolism in diabetes, though debate continues about whether it's truly essential or simply pharmacologically beneficial.

The molecular machinery of chromium metabolism

Chromium's primary metabolic role centers on glucose homeostasis through insulin potentiation. The mineral operates through a sophisticated autoamplification mechanism involving chromodulin, a 1,500-dalton oligopeptide that binds four chromium ions with extraordinary affinity. When insulin binds to its receptor, it triggers chromium movement from blood into insulin-sensitive cells. There, chromium loads onto apochromodulin, creating the active holochromodulin complex that binds directly to the insulin receptor, maintaining it in an activated state and prolonging signal transduction.

This mechanism enhances several critical pathways. Chromium increases insulin receptor autophosphorylation, amplifying the downstream cascade through IRS-1, PI3-kinase, and Akt pathways. It promotes GLUT4 translocation to cell membranes through cholesterol-dependent mechanisms, facilitating glucose uptake. Additionally, chromium inhibits protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B, a negative regulator that normally terminates insulin signals, thereby extending insulin's metabolic effects.

Beyond glucose metabolism, chromium influences lipid homeostasis by correcting hyperinsulinemia-induced defects in cholesterol efflux. It restores ATP-binding cassette transporter-A1 function, enhances apolipoprotein A1-mediated cholesterol efflux, and promotes pre-β-1 HDL generation. Meta-analyses show chromium supplementation reduces triglycerides by 11-27 mg/dL and increases HDL cholesterol by 2-5 mg/dL, with effects most pronounced in individuals with metabolic dysfunction.

The nutrient interaction network shapes chromium function

Chromium's effectiveness depends heavily on its interactions with other nutrients, creating a complex web of synergistic and antagonistic relationships. Vitamin C emerges as chromium's most important partner, significantly enhancing absorption by reducing chromium to a more bioavailable form and preventing oxidation. Studies demonstrate 100mg of vitamin C co-administered with chromium increases plasma levels substantially compared to chromium alone.

Niacin forms another crucial alliance with chromium. Chromium nicotinate shows superior bioavailability compared to other forms, with studies demonstrating enhanced effects on lipid profiles and inflammatory markers. The niacin-chromium combination reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-6, and CRP more effectively than chromium alone, suggesting synergistic anti-inflammatory properties.

Conversely, several nutrients inhibit chromium function. High-dose calcium or magnesium antacids significantly reduce chromium absorption through competitive inhibition. Simple sugars paradoxically increase urinary chromium excretion, potentially depleting body stores – a concerning finding given chromium's role in glucose metabolism. Iron competes with chromium for transferrin binding sites, though supplementation studies show minimal impact on iron status at typical chromium doses.

The complexity extends to macronutrient interactions. Diets high in simple sugars increase chromium losses, while complex carbohydrates preserve chromium status. Protein interactions center on transferrin binding, with 95% of blood chromium bound to this and other plasma proteins. In lipid metabolism, chromium influences fat distribution and may affect the conversion of glucose to stored fat, though effects remain modest.

Mechanisms of metabolic action at the cellular level

Chromium's metabolic effects operate through multiple sophisticated mechanisms. The primary pathway involves enhancing insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity, which chromium accomplishes through direct binding of the chromodulin complex to activated insulin receptors. This binding maintains receptors in their phosphorylated, active state, prolonging and amplifying insulin signaling.

A surprising discovery reveals chromium's glucose uptake stimulation requires reactive oxygen species generation. Chromium treatment increases ROS formation, and this oxidative component appears necessary for its metabolic effects – antioxidants like N-acetyl cysteine abolish chromium's glucose uptake enhancement. This finding suggests chromium works through controlled oxidative signaling rather than purely through insulin receptor modulation.

The mineral also influences cellular glucose transport through non-classical pathways. Chromium promotes GLUT4 translocation via cholesterol-dependent mechanisms independent of traditional insulin signaling proteins. This involves plasma membrane cholesterol dynamics and actin cytoskeletal reorganization, providing an alternative route for glucose uptake enhancement.

At the molecular level, chromium activates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a master metabolic regulator. AMPK activation enhances glucose uptake, fatty acid oxidation, and mitochondrial biogenesis while inhibiting lipogenesis. This positions chromium as a metabolic switch, promoting catabolic over anabolic processes – particularly relevant for metabolic syndrome management.

The chromium-vitamin B12 connection reveals metabolic convergence

While chromium and vitamin B12 lack direct biochemical interactions at the enzymatic level, research reveals important indirect connections through shared metabolic pathways. Both nutrients support cellular energy production through complementary mechanisms – chromium enhances glucose utilization and insulin sensitivity, while B12 enables mitochondrial energy production through its roles in methylmalonyl-CoA mutase and methionine synthase.

Occupational studies provide the most direct evidence of interaction. Workers with chronic chromium exposure show vitamin B12 and folate deficiency accompanied by elevated homocysteine levels. This suggests chromium exposure may disrupt B12 metabolism through oxidative stress mechanisms, creating a functional B12 deficiency despite adequate dietary intake.

The nutrients converge in energy metabolism pathways. Chromium facilitates glucose entry into cells and its conversion to ATP, while B12 enables the citric acid cycle to function properly through its role in converting methylmalonyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA. This complementary relationship explains why commercial supplements often combine both nutrients for "metabolic support" and "cellular energy production."

Clinical applications reveal further connections. Both nutrients are extensively studied in diabetes management – chromium for insulin sensitivity and B12 for preventing deficiency, especially in metformin users. Observational studies associate both nutrients with reduced middle-aged weight gain and improved metabolic parameters. While they work through different mechanisms, their combined effects may provide more comprehensive metabolic support than either nutrient alone.

Current scientific landscape shows evolving perspectives

The scientific understanding of chromium has evolved significantly in recent years, with major debates reshaping recommendations. A fundamental controversy divides American and European health authorities – while the US Institute of Medicine classified chromium as essential in 2001, the European Food Safety Authority concluded in 2014 that essentiality cannot be established. This disagreement reflects the lack of validated biomarkers for chromium status and absence of a clearly defined deficiency state.

Recent meta-analyses (2020-2025) confirm chromium's modest but statistically significant effects on glucose metabolism in type 2 diabetes. A 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found chromium supplements effective for glycemic control. However, effect sizes remain small – typical improvements include fasting glucose reductions of 19 mg/dL and HbA1c decreases of 0.5-1.0%.

The emerging consensus suggests chromium's effects are pharmacological rather than nutritional. At doses of 200-1,000 μg/day used in clinical trials – far exceeding the 25-35 μg adequate intake – chromium acts more like a therapeutic agent than an essential nutrient. This reframing explains why benefits appear primarily in metabolically compromised individuals rather than healthy populations.

Safety remains favorable at typical supplementation doses, with no tolerable upper limit established. However, isolated case reports of kidney and liver dysfunction at very high doses (1,200-2,400 μg/day) warrant caution. The distinction between trivalent chromium (Cr³⁺) used in supplements and toxic hexavalent chromium (Cr⁶⁺) from industrial sources remains crucial for safety assessment.

Conclusion

Chromium orchestrates a complex metabolic symphony, with its primary instrument being insulin sensitization through the chromodulin complex. While not directly interacting with vitamin B12 at the molecular level, both nutrients support energy metabolism through complementary pathways – chromium facilitating glucose utilization and B12 enabling mitochondrial function. The mineral's effectiveness depends critically on interactions with other nutrients, particularly vitamin C and niacin, which enhance its bioavailability and metabolic effects.

Current evidence positions chromium as a modest but meaningful intervention for glucose metabolism in diabetes and metabolic syndrome, though clinical significance remains debated. The ongoing controversy about chromium's essential status reflects our evolving understanding – it may be more accurate to view chromium as a beneficial pharmacological agent rather than a traditional essential nutrient. Future research should focus on identifying biomarkers for chromium status, optimizing nutrient combinations for metabolic health, and determining which populations benefit most from supplementation. For now, chromium remains a fascinating example of how trace minerals can profoundly influence metabolism through sophisticated molecular mechanisms, even as we continue unraveling the full scope of its biological significance.