Cells protect themselves from toxins through an intricate system of sequestration, compartmentalization, and coordinated detoxification that cannot function in isolation but must work in concert with cellular rebuilding processes. Rather than removing toxins one by one, cells employ a sophisticated triage system that prioritizes threats based on immediate danger, available resources, and metabolic needs while maintaining the delicate balance between detoxification and cellular repair.

The complexity of this system reflects evolution's response to the chemical diversity of our environment. Cells face a constant barrage of potentially harmful substances – from environmental pollutants and drug metabolites to the reactive intermediates generated during normal metabolism. The cellular response involves over 500 genes, multiple organelles, and an elaborate network of signaling pathways that must work in precise coordination to maintain homeostasis while preventing cellular damage.

How cells sequester and store toxins

Cellular compartmentalization serves as the first line of defense against toxic compounds, employing specialized organelles and molecular mechanisms to isolate harmful substances from sensitive cellular machinery. Lysosomes, with their acidic environment maintained at pH 5.0 by V-type H+-ATPases, trap weak basic drugs through a process called pH trapping – compounds diffuse across the membrane but become protonated and unable to escape once inside. This mechanism can sequester chemotherapeutics like doxorubicin so effectively that it contributes to multidrug resistance in cancer cells by creating a "sink" that pulls therapeutic compounds away from their intended targets.

The molecular machinery of toxin sequestration involves sophisticated transport systems. ABC transporters, particularly P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) and the multidrug resistance proteins (MRPs), use ATP to actively pump toxins and their conjugates out of cells or into storage compartments. These transporters exhibit remarkable substrate promiscuity, handling diverse chemical structures from heavy metals to complex organic molecules. In plants, the vacuole serves as the primary storage compartment, accounting for up to 90% of cellular heavy metal storage in hyperaccumulator species like Thlaspi caerulescens, which stores 72% of cellular nickel in its vacuoles.

Metallothioneins represent another crucial sequestration mechanism, particularly for heavy metals. These small, cysteine-rich proteins contain approximately 30% cysteine residues, allowing a single metallothionein molecule to bind up to seven divalent metal ions. The binding affinity follows a specific hierarchy – copper > cadmium > zinc – with these proteins serving dual roles in both essential metal homeostasis and toxic metal detoxification. During metal exposure, cells rapidly upregulate metallothionein synthesis through the metal-responsive transcription factor MTF-1, creating a buffer system that prevents free metal ions from damaging cellular components.

Fat cells provide a unique storage mechanism for lipophilic toxins, particularly persistent organic pollutants (POPs) like PCBs, dioxins, and organochlorine pesticides. These compounds partition into adipose tissue based on their octanol-water partition coefficients, with white adipocytes' large lipid droplets serving as reservoirs. This storage can be both protective and problematic – while it sequesters toxins away from metabolically active organs, weight loss can mobilize these stored compounds, causing 46.7% to 83.1% increases in serum POP levels after significant weight reduction, potentially overwhelming the body's detoxification capacity.

The biochemistry of coordinated detoxification

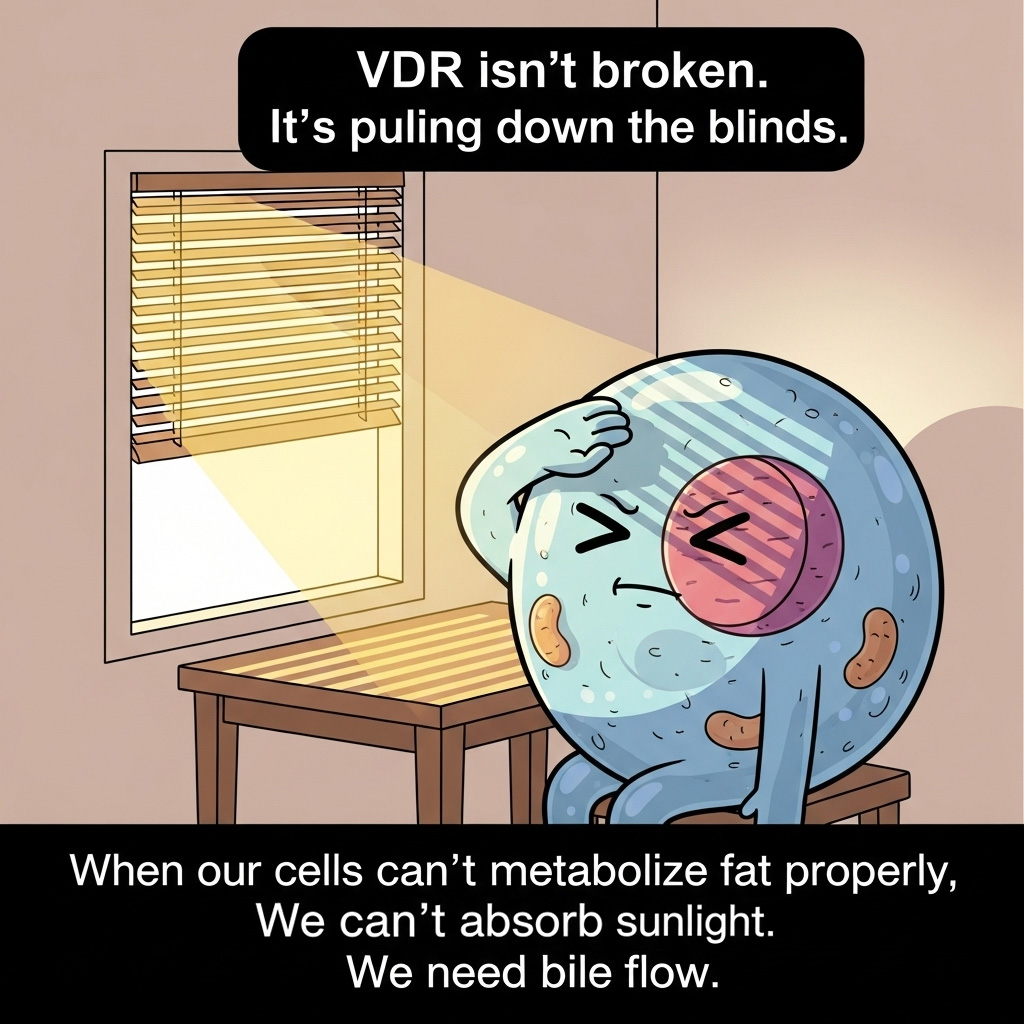

The Phase 1 and Phase 2 detoxification systems exemplify why toxin removal cannot occur in isolation. Phase 1 reactions, primarily mediated by cytochrome P450 enzymes, introduce or expose polar functional groups on lipophilic compounds. However, this process often creates more reactive intermediates than the original toxins – compounds that can damage DNA, proteins, and lipids if not immediately neutralized. The liver alone accounts for approximately 22.8% of whole-body oxygen consumption, with detoxification processes among the most energetically demanding cellular activities.

Phase 2 conjugation reactions must immediately follow Phase 1 to prevent accumulation of these dangerous intermediates. Glucuronidation, accounting for 40% of Phase 2 reactions, requires UDP-glucuronic acid as a cofactor. Glutathione conjugation, catalyzed by glutathione S-transferases, provides crucial protection against electrophilic compounds but depletes cellular glutathione stores that must be continuously replenished. Each pathway requires specific cofactors – sulfation needs PAPS (3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate), methylation requires SAMe (S-adenosyl-L-methionine), and acetylation uses acetyl-CoA. Without adequate cofactor availability or coordinated enzyme activity, toxic intermediates accumulate and cause cellular damage.

The energetic cost of detoxification creates a fundamental constraint on cellular function. ATP-dependent transporters in Phase 3 detoxification compete with other cellular processes for energy. Studies in ERCC1-deficient mice demonstrate that when this balance is disrupted, cells undergo metabolic redesign, rerouting glucose through the pentose phosphate pathway to generate NADPH for detoxification at the cost of normal cellular functions. This metabolic competition explains why detoxification must be carefully balanced with cellular maintenance and repair processes.

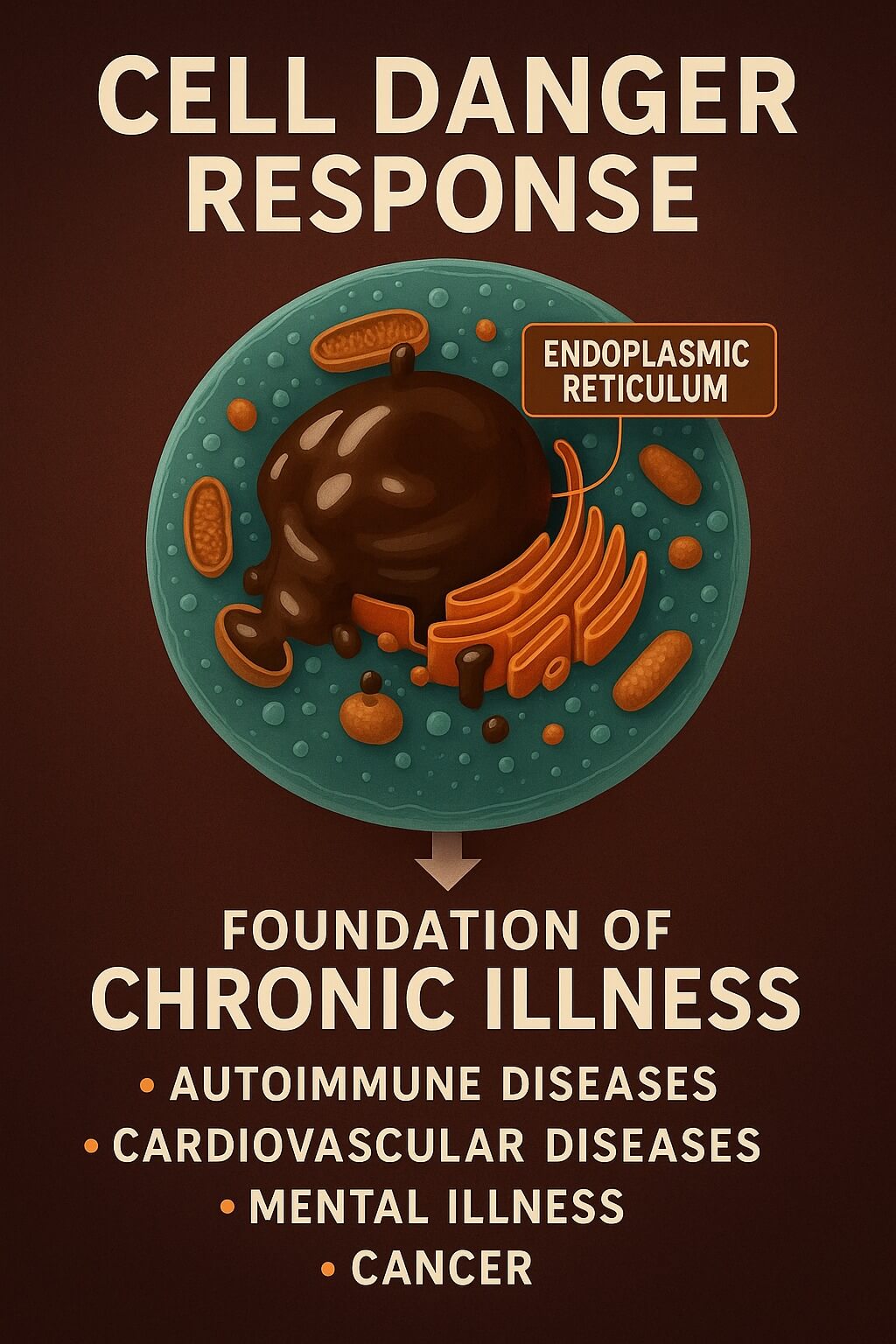

Why detoxification requires simultaneous cellular rebuilding

The generation of reactive intermediates during detoxification creates an immediate need for cellular repair and rebuilding. Cytochrome P450 enzymes generate reactive oxygen species as byproducts, including superoxide radicals and hydrogen peroxide, which damage cellular membranes, proteins, and DNA. The Nrf2-Keap1 pathway responds within minutes, upregulating over 500 genes encoding antioxidant enzymes, detoxification proteins, and repair machinery. Without this coordinated response, oxidative damage overwhelms the cell's repair capacity, leading to dysfunction or death.

Heat shock proteins exemplify the coordination between detoxification and cellular maintenance. HSP70, HSP90, and HSP27 are upregulated during detoxification to protect and refold damaged proteins, maintain protein stability under oxidative stress, and prevent aggregation that could impair cellular function. The heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) pathway coordinates with Nrf2 signaling to ensure both detoxification capacity and cellular protection are maintained simultaneously. This coordination is so critical that its disruption, as seen in ataxia telangiectasia (ATM deficiency), leads to oxidative stress and neurodegeneration.

The unfolded protein response (UPR) provides another layer of coordination, with three branches (PERK, IRE1, ATF6) that reduce protein synthesis load during stress, increase chaperone production, enhance protein degradation capacity, and trigger apoptosis if homeostasis cannot be restored. This system prevents the accumulation of misfolded proteins that could otherwise form toxic aggregates, demonstrating why protein synthesis, quality control, and detoxification must operate in concert.

Cellular membranes and organelles suffer significant damage during detoxification and require constant renewal. The endoplasmic reticulum, where many Phase 1 reactions occur, experiences substantial stress requiring membrane repair and protein replacement. Mitochondria, particularly vulnerable to oxidative damage, must be removed through mitophagy and replaced through biogenesis. The mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPR-mt) activates during detoxification to maintain mitochondrial function while removing damaged components.

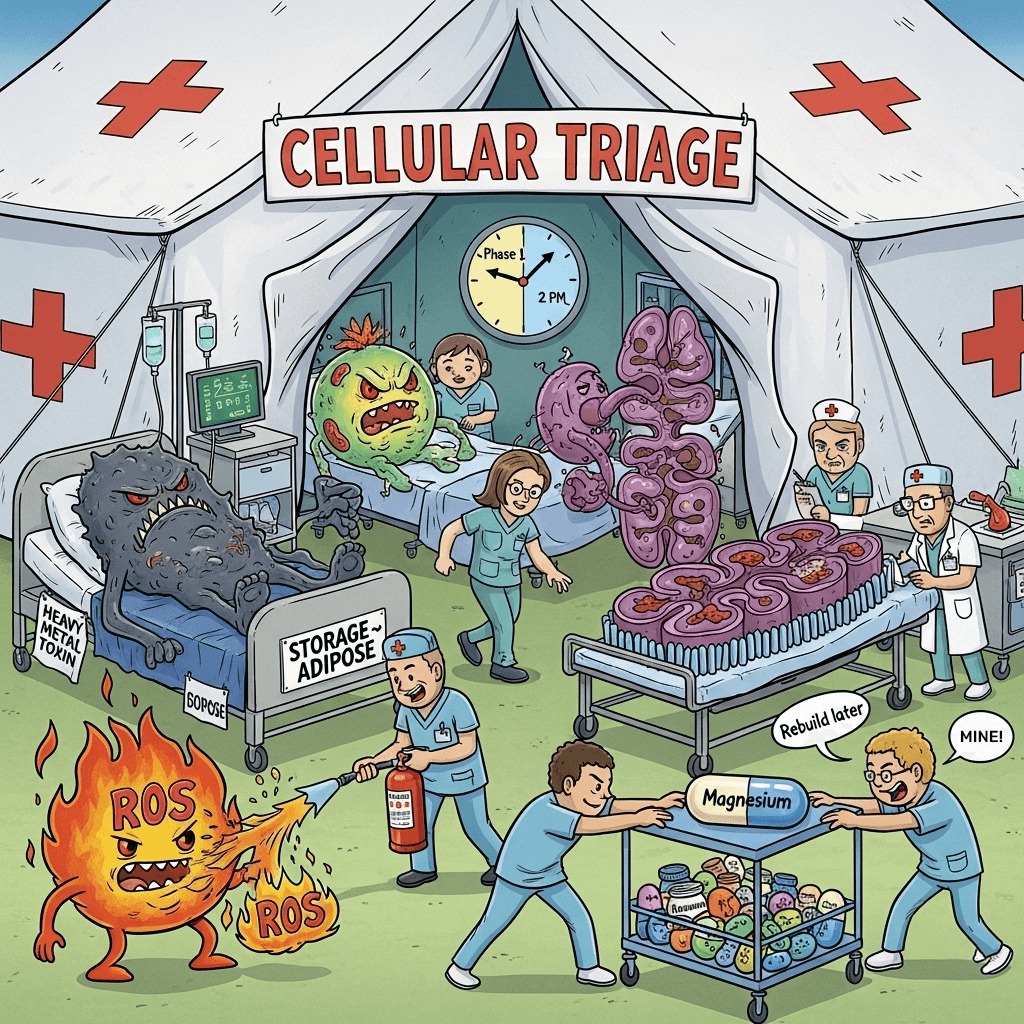

Cellular triage systems for prioritizing toxin removal

Cells employ sophisticated decision-making processes to prioritize which toxins to remove based on current cellular needs and available resources. The cellular "danger sensing" system integrates multiple inputs – ROS levels, ATP/ADP ratios, protein damage markers, and membrane integrity changes – to assess threat levels. Transcription factors like Nrf2, AhR, PXR, and CAR act as xenosensors, each responding to specific classes of toxins with overlapping but distinct gene expression programs.

The Keap1/Nrf2 system exemplifies cellular triage in action. Under basal conditions, low-level Nrf2 activity maintains baseline defense. Moderate stress triggers proportional Nrf2 activation and gene expression, while severe stress causes maximum system activation with complete metabolic reprioritization. This graduated response follows hormetic principles, where low-level toxin exposure (30-60% enhancement above control) actually enhances cellular defense capacity through preconditioning and cross-tolerance development.

Nutrient availability profoundly affects detoxification prioritization. Glutathione synthesis requires cysteine, glutamic acid, and glycine, plus cofactors including B6, magnesium, and selenium. Without adequate nutrients, cells must choose between maintaining basic metabolism and mounting detoxification responses. Under resource limitation, cells follow a hierarchy: maintaining essential functions, addressing immediate cytotoxic threats, then managing chronic low-level exposures. This explains why nutritional status significantly impacts detoxification capacity.

Circadian rhythms add temporal organization to cellular triage. CYP450 expression peaks during active periods, while Phase 2 enzymes show maximum activity during the light phase. The suprachiasmatic nucleus coordinates these rhythms through PAR bZIP transcription factors and clock gene networks, causing xenobiotic toxicity to vary 2-10 fold based on administration time. This temporal coordination aligns detoxification capacity with feeding cycles and metabolic activity, optimizing resource utilization.

Autophagy cleans house during detoxification

Cellular autophagy provides the cleanup mechanism essential for removing damaged components during detoxification. Macroautophagy forms double-membrane vesicles that engulf damaged organelles, protein aggregates, and other cellular debris. Mitophagy specifically targets mitochondria damaged by toxins through the PINK1/Parkin pathway – PINK1 accumulates on depolarized mitochondria, recruits Parkin E3 ubiquitin ligase, and triggers ubiquitination that marks them for autophagic degradation.

The regulation of autophagy involves a delicate balance between mTOR (which inhibits autophagy under nutrient-rich conditions) and AMPK (which promotes autophagy during energy depletion). AMPK directly phosphorylates ULK1 at Ser317 and Ser777 to initiate autophagy while simultaneously inhibiting mTOR through the TSC1/2 pathway. This dual regulation ensures autophagy activates precisely when cells need to recycle damaged components and generate resources for detoxification.

Chaperone-mediated autophagy provides selective degradation of specific proteins containing KFERQ-like motifs, mediated by HSC70 chaperone and LAMP-2A receptor. This pathway targets regulatory proteins and enzymes that may be damaged during detoxification, allowing their selective removal without affecting functional proteins. The specificity of this system exemplifies the precision with which cells manage protein quality during stress.

Autophagy directly supports detoxification by maintaining cellular ATP levels for energy-dependent detox processes, providing amino acids for glutathione synthesis, supporting Phase 1 and Phase 2 enzyme production, and facilitating adaptation to chemical stress. The connection between autophagy and detoxification is so fundamental that impaired autophagy, as seen in various diseases, significantly compromises the cell's ability to handle toxins.

The integrated nature of detoxification systems

The body's detoxification systems work as an integrated network rather than isolated pathways. The liver processes over 75% of systemic detoxification, but relies on the intestines for first-pass metabolism, kidneys for excretion, and adipose tissue for temporary storage. Each organ expresses different combinations of detoxification enzymes optimized for their specific exposure patterns and physiological roles. Hepatocytes show high expression of Phase 1 CYP450 and Phase 2 GST enzymes with extensive MRP2-mediated biliary excretion, while intestinal cells emphasize barrier function with high P-glycoprotein expression.

Cross-talk between signaling pathways ensures coordinated responses across the detoxification network. Nrf2 activation influences AhR signaling, which modulates CAR and PXR expression, creating hierarchical control that prevents conflicting cellular responses. The extensive interaction between Nrf2, UPR, heat shock response, and DNA damage response pathways ensures that detoxification, protein quality control, and cellular repair proceed in concert rather than competition.

The tail-anchored protein system provides a molecular paradigm for how cells make triage decisions at the molecular level. Client proteins exist in an uncommitted state bound to SGTA chaperone, with kinetic competition determining whether they undergo rapid transfer to TRC40 for productive folding (biosynthesis priority) or slower capture by Bag6 for degradation (quality control). This time-encoded decision-making process operates throughout the detoxification system, with reaction kinetics and molecular interactions determining cellular responses to toxin exposure.

Iodine as a gentle catalyst for coordinated detoxification

Iodine offers a unique approach to gradually activating our cellular detoxification machinery at a pace our bodies can manage. Rather than forcing aggressive toxin removal that could overwhelm our systems, iodine works as a metabolic catalyst that slowly "wakes up" dormant detox pathways while providing the cellular energy needed to process what gets mobilized.

At the cellular level, iodine influences detoxification through multiple mechanisms. It enhances mitochondrial function and ATP production, providing the energy currency our cells need for Phase 3 transport proteins and cellular repair. Through its effects on thyroid hormone production, iodine modulates the expression of detoxification enzymes – T3 hormone upregulates hepatic CYP450 enzymes, glutathione S-transferases, and sulfotransferases in a controlled manner. This gradual upregulation allows our cells to increase their processing capacity without creating a sudden flood of reactive intermediates.

Iodine's antimicrobial properties help reduce the burden on our detox systems by addressing underlying infections that may be contributing to toxic load. It has selective toxicity against pathogenic bacteria, fungi, and certain parasites while supporting beneficial microbiome balance. By reducing this microbial burden, our cells can redirect resources from immune responses to actual toxin processing and cellular repair.

The halogen competition aspect of iodine supplementation provides another layer of gentle detoxification. Iodine can displace toxic halides like bromide and fluoride that have accumulated in our tissues over years of exposure. This displacement happens gradually as iodine saturation increases, allowing our kidneys to excrete these halides at a manageable rate rather than causing a sudden mobilization that could trigger detox reactions.

Perhaps most importantly, iodine supports the cellular triage system we've been discussing. It doesn't force our cells to dump everything at once but rather enhances their ability to make intelligent decisions about what to process when. The improved thyroid function optimizes our circadian regulation of detox enzymes, while enhanced mitochondrial function ensures adequate ATP for both detoxification and rebuilding processes. This allows our cells to work through their backlog of stored toxins methodically – clearing out the "funk" as our currently built machinery can handle it, then upgrading that machinery as resources become available.

The key to using iodine effectively for detoxification lies in starting slowly and allowing our bodies to adapt. Beginning with small doses (often in the microgram range) and gradually increasing allows our cells to upregulate their detox capacity in step with the mobilization of stored toxins. This approach respects the fundamental principle that our cells must rebuild while they clear – we're not just removing toxins but supporting the entire integrated network of cellular processes that maintain our health.

Conclusion

Cellular toxin management represents one of biology's most sophisticated protective systems, integrating storage, detoxification, repair, and cellular rebuilding into a coordinated response that maintains homeostasis while preventing damage. The requirement for coordination stems from fundamental biological constraints – the energetic cost of detoxification, the generation of reactive intermediates, the need for continuous cellular maintenance, and the complex prioritization required when facing multiple simultaneous threats.

Rather than simple, linear toxin removal, cells employ dynamic triage systems that assess danger levels, allocate resources based on priority hierarchies, adapt to chronic exposures through hormetic mechanisms, and coordinate timing with metabolic cycles. Tools like iodine can serve as gentle catalysts that work with these natural systems, gradually enhancing our cellular machinery's capacity to clear accumulated toxins while maintaining the delicate balance between detoxification and rebuilding. Understanding these integrated mechanisms reveals why effective detoxification strategies must support not just toxin removal but the entire network of cellular processes that maintain health in our chemically complex world.